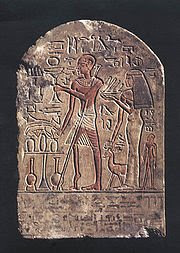

Polio has afflicted humans since ancient times. A carved stone tablet found in Egypt, dating from roughly 1500 bc, depicts a man whose withered, deformed leg and foot are characteristic of paralytic polio. Descriptions of cases consistent with polio also date from ancient Greek and Roman times.

Polio has afflicted humans since ancient times. A carved stone tablet found in Egypt, dating from roughly 1500 bc, depicts a man whose withered, deformed leg and foot are characteristic of paralytic polio. Descriptions of cases consistent with polio also date from ancient Greek and Roman times.One of the first accurate descriptions of polio was made by the British physician Michael Underwood. In 1789 he noted cases of “debility of the lower extremities, [which] usually attacks children previously reduced by fever.” Around 1850, German physician Jacob von Heine named the condition infantile paralysis because the disease seemed to affect mainly young children.

Until the 19th century, polio was a common infection that rarely caused paralysis in children. As the 1800s ended, however, the nature of the disease changed. Ironically, this change occurred as a result of gradual improvements in sanitation and plumbing. Poor sanitation had constantly exposed people to poliovirus and other fecal contaminants.

Most people, therefore, developed natural immunity after early and usually harmless exposure to the virus. Better plumbing and sanitation broke the cycle of exposure and natural immunity. Thus, people tended to be exposed to the virus at a later age, when the effects of the disease were more serious. The first large-scale polio epidemics hit Scandinavia in 1887 and the United States in 1894.

The effects of polio have been known since prehistory; Egyptian paintings and carvings depict otherwise healthy people with withered limbs, and children walking with canes at a young age. The first clinical description was provided by the English physician Michael Underwood in 1789, where he refers to polio as "a debility of the lower extremities".

The work of physicians Jakob Heine in 1840 and Karl Oskar Medin in 1890 led to it being known as Heine-Medin disease. The disease was later called infantile paralysis, based on its propensity to affect children.

Before the 20th century, polio infections were rarely seen in infants before six months of age, most cases occurring in children six months to four years of age. Poorer sanitation of the time resulted in a constant exposure to the virus, which enhanced a natural immunity within the population.

In developed countries during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, improvements were made in community sanitation, including better sewage disposal and clean water supplies. These changes drastically increased the proportion of children and adults at risk of paralytic polio infection, by reducing childhood exposure and immunity to the disease.

No comments:

Post a Comment